Trans 101: Everything You Think You Know (But Probably Don’t)

Got a rainbow sticker? Follow trans creators? Have trans friends? Cool. But if you’re like most people—even the well-meaning ones—you probably know just enough about trans people to be dangerous. In this episode, we’re dismantling the “born in the wrong body” narrative and exploring what being trans actually means. With help from University of Victoria transgender studies chair Dr. Aaron Devor, paleontologist Riley Black, PhD student Hibby Thach, and comedian Charlie James, we’re breaking down sex vs. gender vs. gender expression, debunking the “social contagion” myth, and explaining why asking “but have you had The Surgery?” is never okay. Trans people are rarer than redheads, but somehow they’re at the center of a political firestorm—so let’s actually understand what we’re talking about.

Video version:

More from Aaron Devor:

More from Riley Black:

- Website

- Order her latest book, The Last Days of the Dinosaurs

- Bluesky

More from Hibby Thach:

More from Charlie James:

- Website

- Order his book, I’m Just a Little Guy: How to Escape the Horrors and Get Back to Dillydallying

- TikTok

Citations and further reading:

- A sex difference in the human brain and its relation to transsexuality

- Transsexuality Among Twins: Identity Concordance, Transition, Rearing, and Orientation

- Gender dysphoria – Symptoms and causes – Mayo Clinic

- Depression Induced by Total Mastectomy, Breast Conserving Surgery and Breast Reconstruction: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

- Mental health after orchiectomy: Systematic review and strategic management

- Amanda Bynes on the Cover of PAPER Break the Internet

- US Trans Survey

From the US Trans Survey:

TRANSCRIPT

Introduction: The “born in the wrong body” trope

[00:00:00] Ashley: I know just enough about trans people to be dangerous. Dangerous because the illusion of understanding has kept me from real understanding, dangerous because good intentions plus bad information can cause actual harm. And I’m not alone. There are a lot of well-meaning people who think they get it, but really don’t.

[00:00:28] Ashley: I’m not trans myself, but I run in progressive circles. I have trans friends. I follow trans people on social media and read about their experiences of being misgendered or how scary it is to be living in this political environment. I’ve got a rainbow sticker on my water bottle that says you’re safe with me.

[00:00:46] Ashley: I thought I was one of the good ones.

[00:00:49] Ashley: But I’ve been wrong about a lot. For instance, I thought I knew that trans people felt like they were born in the wrong body. That they felt dysphoria and disgust every time they looked in the mirror until the day they finally decided to change that body to become the gender they truly were.

[00:01:05] Ashley: Roll credits.

[00:01:08] Ashley: But it turns out that this tidy storyline that we get in movies and TV shows is only one piece of the puzzle. It’s some people’s experience, don’t get me wrong. But there are a lot of other ways to be trans, and believing this is the only way is actually harmful.

[00:01:24] Ashley: It means that if that person’s gender identity shifts over time or if they like their body the way it is, or if they don’t wanna transition to male or female, but instead wanna throw out the binary altogether, we don’t get it. It’s not taken seriously.

[00:01:42] Ashley: I am making this series for people like me who know just enough to be dangerous. And for people who don’t know but wanna know. And let’s face it for people who need help debating family during the holidays, I did a listener survey. There are a lot of you.

[00:02:00] Ashley: So let’s learn together. I’m Ashley Hamer Pritchard, and this is Taboo Science, the podcast that answers the questions you are not allowed to ask. And Trans 1 0 1 starts right now.

Aaron Devor introduction

[00:02:32] Ashley: You’d be forgiven for believing the whole born in the wrong body thing. For a long time, that was the only line that could get a trans person medical care.

[00:02:41] Aaron Devor: You had to say that, or something very close to that. Or the people who were the gatekeepers to medical treatment would not take you seriously.

[00:02:50] Ashley: That’s Aaron Devor.

[00:02:52] Aaron Devor: I am the chair in transgender studies at the University of Victoria, and I use he, him pronouns. People who feel they need to transform their body as much as medical science will allow or can facilitate, are definitely doing that.

[00:03:09] Aaron Devor: But there’s a lot more trans people out there than that, today. And not everybody feels that their body is the problem. They feel like they need to live their lives as a gender that they identify with.

Riley Black introduction

[00:03:26] Riley Black: It’s so much more complicated and multifaceted.

[00:03:30] Ashley: Riley Black is a trans woman, paleontologist and author of many, many books about dinosaurs, and she echoes that from her own life.

[00:03:39] Riley Black: wasn’t in the wrong body, but my body’s finally being given what it needed that it didn’t have before, and now I can start to think about, well, what feels good for me for how I want to approach the world? And is that strictly sort of within the expectations of what I sense like women are expected to do in my culture and whether I wanna defy that in those terms or whether this is more just freeform self-creation? I feel for many of us, like as we transition that that’s part of the change is not just kind of, like jumping from one box to another, but you have the whole sandbox to play with and it can continue to unfold.

Transgender definition and prevalence

[00:04:12] Ashley: But before we go any further, let’s make sure we’re all on the same page with some basics.

[00:04:22] Ashley: Transgender is an umbrella term that describes a variety of identities for people whose gender doesn’t align with their sex assigned at birth.

[00:04:32] Ashley: If you’ve been following the news in 2025, you may have gotten the impression that trans people are everywhere, but they’re actually a really, really small percentage of the population. One of the best sources we have for this number comes from the Canadian census.

[00:04:47] Aaron Devor: Canada was the first country to do a census where they asked a two part question. They asked what was your sex assigned to you at birth, what is your current gender identity?

[00:05:00] Ashley: this was a really big deal because a census can uncover what a scientific study can’t. Studies generally have to use a smaller sample of the population and then make estimates from there.

[00:05:12] Aaron Devor: Census doesn’t get everybody, but it’s the closest thing we have to talking to everybody in the country. And what they found was that trans plus,

[00:05:21] Ashley: that is trans non-binary and all the other gender identities that don’t align with the person sex assigned at birth.

[00:05:28] Ashley: Their overall percentage of the Canadian population was

[00:05:32] Aaron Devor: one third of 1%. So, at that time, that was just over a hundred thousand people.

[00:05:38] Ashley: 0.3%. Now this varies by generation, with more trans people showing up in younger generations, gen Z was closer to 0.8%. It’s also likely to be an underestimate since many trans people are understandably wary of telling the government about their identity.

[00:05:58] Ashley: And still. Redheads make up one to 2% of the global population. Left-handed people make up 10%. Trans people are a fraction of a fraction of the population, and yet, right wing lawmakers are spending significant chunks of their time trying to make sure they don’t have rights.

Why are more young people trans?

[00:06:18] Ashley: Those lawmakers and people who agree with them often take the fact that there are more trans people coming out in younger generations and claim that it’s some sort of social contagion.

[00:06:28] Ashley: That social media, liberal school teachers, or drag story hour are turning our children trans. While we know that simple exposure to a trans person won’t turn you trans if you weren’t trans already, it’s worth asking why do there seem to be so many more trans people today than in the past?

[00:06:46] Aaron Devor: I do a lot of historical work. And I’ve talked to a lot of people in many generations, and I’ve heard stories over and over again about people who had feelings, thought they were the only one in the world who felt this way, had no idea what to call it. Were terrified to tell anybody what they felt because it just seemed so bizarre. They’d never heard of it. They’d never seen it. It was just unthinkable. And people who had those experiences, the reason I ended up being able to talk to them is because maybe they were in their thirties, their forties, or fifties, even their sixties, the world around them started to change. They learned, oh, there’s a name for this. Oh, there’s other people like me. Oh, I can do something about it. And their lives changed.

[00:07:32] Ashley: Aaron knows this landscape personally as well as professionally. He’s transgender himself and his decades of research have been informed by both his academic expertise and his own lived experience.

[00:07:45] Ashley: Meanwhile, kids were being born and raised in a society that’s more welcoming of trans people.

[00:07:51] Aaron Devor: And so now we have whole generations who are growing up in a world where they know about it from being very little because it’s on TV shows, it’s in films, it’s all over social media, it’s all over traditional media. There’s kids in their classrooms, they’re parents of somebody they know. So it’s all around them.

Why are people trans in the first place?

[00:08:11] Ashley: With more people able to recognize and talk about their experiences, it’s natural to wonder. What is it that makes someone trans?

[00:08:23] Aaron Devor: That’s a question that is hotly debated. Uh, It has not been settled. There is a strong tendency among scientific opinion to believe that we will find, I’m gonna emphasize, will find ’cause we have not yet found, a biological basis for people who are trans.

[00:08:46] Ashley: There are several studies that support this idea. In 1995, researchers published a study in Nature examining the brains of transgender women after death. They found that a part of the brain involved in sexual behavior looked more like that of cisgender women than cisgender men.

[00:09:03] Ashley: In other words, the brain structure matched the gender these individuals identified with, not the sex they were assigned at birth. Since then, many studies have found differences in brain structure between trans people and cis people.

[00:09:16] Ashley: But it’s important to note that some of these studies don’t account for possible changes brought about by hormone therapy. And also neuroscience is complicated. You couldn’t look at a scan of my brain and say, without a doubt that I’m a woman.

[00:09:31] Ashley: There’s also some evidence that identical twins are more likely to both be transgender than fraternal twins. Which suggests that there could be a genetic component to being trans.

[00:09:41] Ashley: But that evidence has limitations too.

[00:09:45] Ashley: But supposing there is a biological basis.

[00:09:49] Aaron Devor: The theory is that when a human fetus is developing, that there are different stages for the development of genitalia, which is what we usually use to decide sex and gender, and brain structures that are associated with what we usually describe as masculinity and femininity or gender identity as a man or a woman. And they develop at different stages.

[00:10:18] Aaron Devor: And so the theory, with some evidence, is that you get a mismatch. So the genitalia develop in one direction, the brain develops in another direction. Why does that happen? Well, there’s even less evidence for why that happens. That’s a pretty strong theory at this point.

[00:10:36] Aaron Devor: But as I said before, not enough to say, oh, we’ve figured it out. It’s definitive.

[00:10:41] Ashley: Then there’s the nature versus nurture debate. Not to say it’s just biological or just social, but how much of each plays a role?

[00:10:50] Aaron Devor: Most people who work in the field, not just trans but in human development, will agree that it’s a combination of nature and nurture that makes us who we are.

[00:10:59] Aaron Devor: We haven’t reached consensus yet that there’s a biological thing happening. But then what’s your experience in life? And so, again, I’m talking not proven here and not consensus yet, uh, but there are some people who will come into life and that disjuncture that I just described is very strong and will assert itself no matter what happens in their upbringing and their life experience.

[00:11:24] Ashley: That is to say there are people who, regardless of whether they’re raised around out trans people or in an accepting environment, will realize that they’re not the sex assigned to them at birth and decide to transition no matter the challenge.

[00:11:37] Aaron Devor: And then there’s a whole lot of other people where that disjuncture is there, but it’s not all that strong. So what happens in their upbringing and their lives and their experiences will have a moderating effect on whether they express that or how they express that.

[00:11:53] Ashley: Like Dr. Devor said, if you were trans in a time and place where you didn’t have a word for it, you didn’t know anyone else like you, and you risked serious persecution for coming out, not only would you be less likely to come out, but you’d be less likely to even identify what you were feeling.

“Egg cracks”

[00:12:09] Ashley: Here’s Riley again.

[00:12:10] Riley Black: Is kind of funny, right? Because once you come out and embrace that you’re, you’re trans and you know are working out your gender, which never really stops anyway. Keep seeing all these little egg cracks.

[00:12:21] Riley Black: I

[00:12:21] Ashley: Egg. A person who is transgender but hasn’t yet realized it, that is, they haven’t hatched into their true self. Egg cracks then, are the little signs that the person is trans along the way. It’s truly one of my favorite pieces of trans slang, maybe because it makes me think of every trans person as a Tamagotchi who you need to feed and care for until they finally hatch into their final form.

[00:12:46] Ashley: Anyway, one of Riley’s egg cracks came in the form of a 1970s monster movie called the Terror of Mechagodzilla.

[00:13:01] Riley Black: And in that film there’s a young woman who basically is turned into a cyborg and she’s given control over the villain, this monster Mecca Godzilla. And I remember seeing this as a kid like, I wish I could be her. mean, of course that’s impossible. I can’t be a cyborg. I can’t control giant robot monsters that shoot rainbows outta their eyes. Why would I give this a second thought? But there are all these little, you know, what we know as egg cracks that preceded coming out.

[00:13:29] Riley Black: The thing that really broke it for me, I think if I have to pick the pivotal moment where I embrace myself.

[00:13:35] Riley Black: I was in, uh, Yellowstone National Park, and it was in the Mammoth Campground, overlooking you know, a river in a mountain range. And I like to bring a stack of books with me about hip high. And I just finished, Laura Jane Grace and she’s the singer of Against Me! and has a new solo album coming out and stuff, you know, punk rocker.

[00:13:54] Riley Black: She wrote a memoir called Tranny about her experiences, and I closed the last page of this book. It’s like, I think this is me. Like there’s so much in here that resonates that I just told myself would be impossible or I can’t do, or it’s gonna make life too complicated. So it was really not even necessarily realizing that I was trans, but that, that I could do it.

[00:14:13] Riley Black: That I could transition that it could be the self that I feel.

[00:14:17] Ashley: Even after that, Riley still took her time to come out. She was married to an unsupportive partner and she had to get divorced before she felt comfortable physically transitioning. For every Riley out there, there’s also a trans person who didn’t watch that monster movie or read that memoir or divorce their unsupportive spouse.

[00:14:37] Ashley: That’s the role life experience can play in a trans identity.

[00:14:41] Aaron Devor: And so we see a huge range of gender expressions among people who do identify as some kind of transgender and a huge range in terms of what point in their lives do they come to identify as trans, how much do they wanna do about it?

[00:14:55] Aaron Devor: You know, there are people who identify as trans privately, maybe with a couple of friends, and never tell anybody. And that’s okay for them. And then there’s other people who feel compelled to make various changes that can be quite dramatic and have significant impacts on their lives and the lives of people around them.

Sex, gender, and gender expression

[00:15:10] Ashley: To make sense of all this, we need to go back to the fundamentals. What’s the difference between sex and gender?

[00:15:17] Aaron Devor: The most commonly used determiner of sex is simply genitalia. There are more subtle features that we could look at if that’s not a good enough, uh, measure. But usually sex refers to bodily characteristics, gender refers to how someone feels that they fit into the expectations that are usually related to sex.

[00:15:39] Aaron Devor: And so we have in our society a bunch of expectations that if you have male genitalia, you will behave in a certain way. You’ll dress in a certain way, you’ll talk in a certain way, et cetera, et cetera.

[00:15:50] Ashley: As the saying goes, sex is what’s between your legs. Gender is what’s between your ears. So by definition, you can’t tell what someone’s gender is just by looking at them. The only way to know is by asking.

[00:16:03] Aaron Devor: In everyday life, we don’t go around asking people all the time what is your gender? And so what we use is a proxy for trying to figure out what somebody is is their gender expression. So gender expression is how you show to other people what your gender identity is.

[00:16:21] Ashley: We make assumptions about a person’s gender based on their gender expression, which is also sometimes called gender presentation, but even their gender expression may not match the gender they identify as. That is, it may not match their gender identity. Why? Because it’s tough out there.

[00:16:37] Aaron Devor: Sometimes someone’s gender expression doesn’t match their gender identity because they feel unsafe to express the gender that they feel because there’s all sorts of discrimination and stigma in society for people whose gender identity changes or gender expression changes, and there’s stigma for those where it doesn’t match in the way that people think it should match.

[00:16:59] Ashley: So sex is what’s between your legs. Gender is what’s between your ears. Gender expression is what you display to the world. These can all be different.

[00:17:09] Ashley: For example, one signifier we use to assume someone is a man, is facial hair. But you can have facial hair and identify as a woman. PCOS can cause facial hair in cis women, as can simple genetics. We just tend to remove that facial hair as part of our gender expression. I mean, I’ve definitely been known to pluck a chin hair or three. But some choose to keep their facial hair and they’re still women. Just ask Hibby Thach.

Hibby Thach introduction

[00:17:42] Hibby Thach: For me, something about my mustache has always felt right to me, just like throughout my journey as like a non-binary person throughout my journey as a trans woman. Something about the mustache is just aesthetically pleasing to me. Like there’s some like symmetry going on in my face.

[00:17:58] Ashley: Hibby is a third year PhD student at the University of Michigan, and her transition journey didn’t start until she was in college.

[00:18:05] Hibby Thach: I went to art school for creative writing and while there I was around a lot of different, like queer and trans people as well. And I started to question, you know, being a man, I was like, oh, maybe I’m non-binary.

[00:18:19] Ashley: Non-binary, a gender identity that is not exclusively man or woman. We’ve got a whole episode on non-binary identities coming up later.

[00:18:28] Hibby Thach: So for a few years I identified as non-binary. I went by like they, them pronouns, but I didn’t really change anything about my appearance. But about three years ago, I started hormones. And then I started being like, okay, I think maybe I’m more feminine and maybe I’m not just non-binary. Maybe I am like a trans woman.

[00:18:47] Hibby Thach: But then, maybe a little over a year into like taking hormones was when I started actually experimenting with like gender expression, changing my appearance up.

[00:18:57] Ashley: Before, Hibby had a gender expression that might be read as masculine. She had short hair and she wore traditionally masculine clothing, but then she started wearing makeup and letting her hair grow.

[00:19:08] Hibby Thach: And then it’s just been like this last year honestly, where I’ve started wearing more feminine clothing, like dresses, and like actually wearing clothes that fit my changing body. And now I’m at a place where I am fully identifying as a trans woman. I am, don’t identify as non-binary anymore, um, but respect to the non-binary people, I guess.

Gender expression in cis people

[00:19:28] Hibby Thach: Gender expression isn’t just for trans people. It’s also for people who are cis or cisgender, which means their gender identity matches their sex assigned at birth.

[00:19:38] Hibby Thach: Cis people do gender expression too. We just don’t call it that. I’m a cis woman and doing my hair and makeup helps me present as more feminine or femme than when my face is bare and my hair is in a ponytail. I just feel better that way. I have more confidence when I interact with other people because I feel like I’m presenting the best version of who I am.

[00:20:00] Hibby Thach: I can also change my gender expression. I’m a jazz musician, and when I’m going to a jam session where I’ll be the only woman, I’ll do things to present as slightly more masculine or masc. I’ll choose pants over a dress and I’ll speak in a lower register.

[00:20:15] Hibby Thach: Not because that’s my true self, but because over years of interacting with male jazz musicians, I’ve learned that this gender presentation is what gets me taken seriously.

[00:20:24] Hibby Thach: Cis men engage in gender presentation too. The choice to wear a beard, the choice to cut their hair short. The choice to avoid traditionally feminine colors like pink and purple. These are all ways cis men express their gender.

Gender dysphoria

[00:20:42] Hibby Thach: Likewise, cis people can also experience a form of gender dysphoria. The official definition for gender dysphoria is a sense of distress from a mismatch between your gender identity and your sex assigned at birth.

[00:20:55] Hibby Thach: The way this is usually portrayed is similar to the born in the wrong body trope. A trans person hates the body they were born in and can’t feel peace until it’s different, but for many it’s more nuanced. Comedian Charlie James is a trans man who describes his dysphoria this way.

[00:21:11] Charlie James: I was like about to go to college and I was identifying as like a bisexual woman question mark. Like I wasn’t really ready to look at gender too much. And I knew I felt physical dysphoria, but I wasn’t totally sure of like what that was.

[00:21:27] Charlie James: And, I went to see an improv show with my dad, and it was an all male team, and they walked on stage and they were all wearing, they’re, they’re improvisers, they’re all wearing like flannel button-ups. And I was like, oh, I love the way that their shirts fit them, which was so weird. They all had very different bodies and like shirts fit them in varying different ways.

[00:21:48] Charlie James: But I was like, there’s just something about like the shirt sits on them and then it’s flat. I want that. And it took me not long to be like, oh, I hate having boobs. They gotta go. That’s what’s going on.

[00:22:05] Ashley: While dysphoria is a characteristic experience of trans people, it’s not totally unique to them. It’s pretty common for cis people to feel distress or even depression after the removal of a secondary sex characteristic, like after breast cancer or testicular cancer. This is a kind of gender dysphoria. We associate women with having breasts and men with having testicles and without them, a cis person’s physical appearance doesn’t match their gender.

[00:22:32] Ashley: And while I didn’t have the words for it, I remember feeling gender dysphoria during puberty, just the cis version. I remember wanting to have boobs and a curvy figure, and I was frustrated that I still had the body of a 12-year-old girl.

[00:22:47] Ashley: Maybe one of the most dramatic experiences of gender dysphoria by a cis person is the story of when Amanda Bynes dressed as a boy for the movie She’s The Man. The movie is a modern adaptation of Shakespeare’s 12th Night, where a girl disguises herself as her twin brother.

[00:23:04] Ashley: Here’s a quote from Amanda Bynes’ interview with Paper Magazine.

[00:23:08] Ashley: When the movie came out and I saw it, she says, I went into a deep depression for four to six months because I didn’t like how I looked when I was a boy. She paused. I’ve never told anyone that. Seeing herself with short hair and sideburns was quote, a super strange and out of body experience. It just really put me into a funk end quote.

[00:23:30] Ashley: Imagine living your entire life as a gender that doesn’t match the one you feel like inside. That’s gender dysphoria.

Medical transition: hormones

[00:23:38] Ashley: That’s why trans people can go to such great lengths to get their appearance to match their identity. What lengths? Glad you asked. Here’s Aaron Devor again.

[00:23:55] Aaron Devor: So most people, when you say trans, what they think is, hormones and surgeries. And as we discussed a little earlier, there’s a whole range of what people might do. Some people will just, change their name, change their hairstyle, and their clothing.

[00:24:11] Aaron Devor: And that’s sufficient for them to express the gender that they feel and to be recognized as the gender they feel themselves to be.

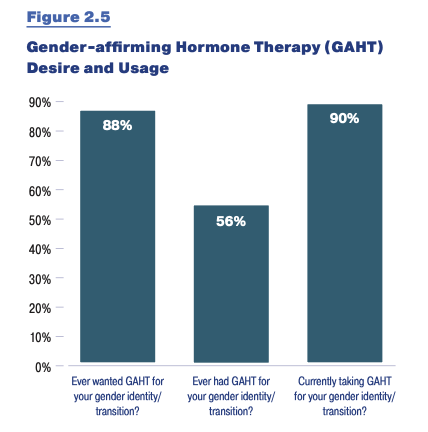

[00:24:25] Ashley: We actually have some idea about how many trans people in the US use hormones thanks to the US Trans Survey. A survey of more than 90,000 trans and non-binary people performed in 2022 and published in 2025. It found that only 56% of respondents had ever had gender affirming hormone therapy, though 88% said they wanted it. That’s evidence that not everybody wants it and even fewer actually get it, which I guess shouldn’t be surprising considering the state of healthcare in general and gender affirming healthcare in particular.

[00:25:01] Aaron Devor: There’s hormones that masculinize the body and there’s hormones that feminize the body. Hormones do a lot and they do even more for trans-masculine people than they do for trans-feminine people.

[00:25:14] Ashley: Someone transitioning to male might take testosterone, which will give them a lower voice, more body hair, and a redistribution of muscle and fat, which can give them a more masculine physique. Someone transitioning to female might take a form of estrogen, which will give them more body fat and a more feminine body fat distribution, slower body hair growth, and even breasts.

How many have surgery?

[00:25:35] Ashley: To go further, some trans people decide to have surgery, which is even rarer than hormone therapy, turns out.

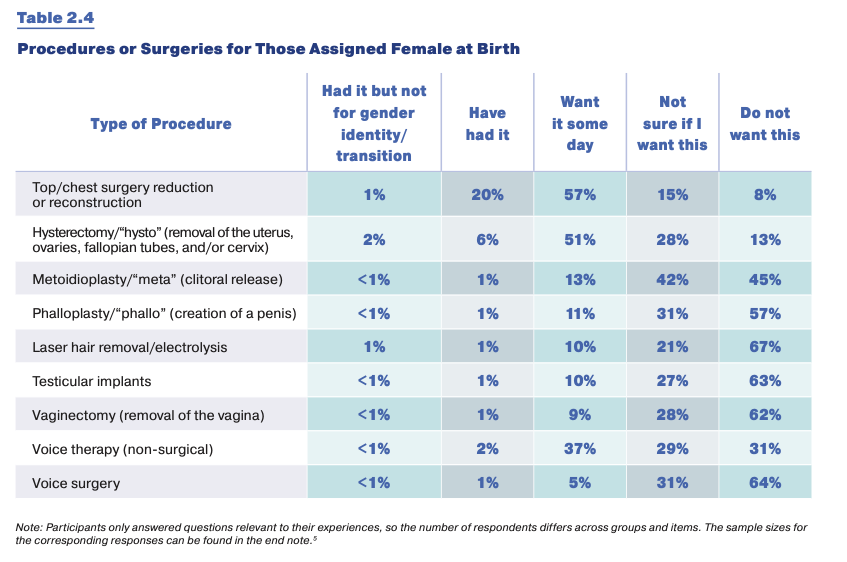

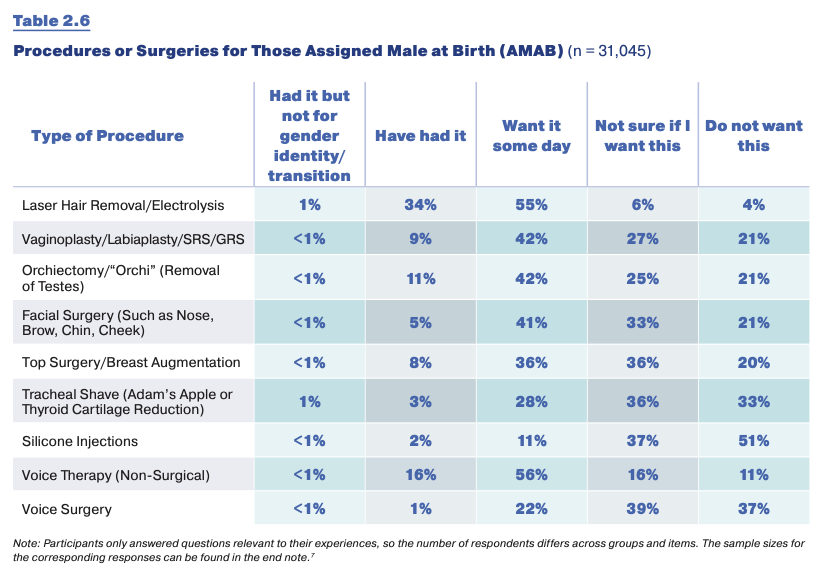

[00:25:42] Ashley: For trans people assigned male at birth, the proportion who had had genital or bottom surgery of any kind topped out at 11%. For trans people assigned female at birth, the rates were even lower. 1% for each kind of bottom surgery. Though, 20% reported having a breast reduction, also known as top surgery. Though again for all of these surgeries, many more want it but just haven’t gotten it.

[00:26:10] Aaron Devor: So when you’re looking at somebody, talking to somebody, if you’re thinking about getting into a sexual relationship with somebody who is, binary transgender, and by that I mean is to someone who is every intent to be taken as a man or a woman, not non-binary, in between somewhere, very few of them are going to have had genital surgery.

[00:26:32] Aaron Devor: And so for some people they look at that and they say, well, then they’re not really a man or a woman because you have to have the genitalia to be a man or a woman. But I can tell you if you met these people and you spent any time with ’em, you wouldn’t question whether they’re men or women, as they present themselves.

[00:26:52] Ashley: My hope is that statistics like these will satisfy any morbid curiosity that might lead you to ask a stranger what’s in their pants.

[00:27:00] Ashley: It’s not really your or my or anyone’s business, and it’s just as rude to ask a trans person about their genitals as it is to ask you about yours.

[00:27:09] Aaron Devor: Genitalia is a personal, private thing and sometimes it requires some negotiation if you’re in a sexual situation with somebody. Um, but probably wouldn’t be in that situation in the first place if the other person didn’t find you attractive.

[00:27:25] Aaron Devor: In the vast majority of situations, there’s really no reason to not accept a person as they wish to be presented. It’s just common decency. It’s just being human to respect somebody’s identity, to respect somebody’s request to be treated with dignity.

Wrap-up

[00:27:57] Ashley: When I started working on this episode, I thought I knew what it meant to be trans. I thought there was one story, one way to do it right. But what I learned is that being trans is as varied and complex and human as any other part of the human experience. And for all the challenges we’ve talked about today, there’s something else that’s just as important to understand. Living as your true self makes people really happy.

[00:28:25] Riley Black: I couldn’t smile pre-transition.

[00:28:30] Riley Black: I remember even as like month one. I think of being on HRT and my girlfriend came out to visit out here in Utah. I took her to Dinosaur National Monument, one of my favorite places in the world. That big bone wall out in the desert that you can go and see, you know, from 150 million years ago.

[00:28:45] Riley Black: Things like Stegosaurus and Diplodocus all laid out in front of you. I love it there. I wanted to take a selfie and smile and just kind of like, trying to arrange my face mentally to figure out how, how do I look like I’m happy in this photo. And now whenever I go back, it’s like beaming. I can’t hold it in. And I can look at those pre-transition photos and just, I can see the person who was in there kind of like waiting like a bit of a chrysalis.

[00:29:13] Ashley: The person who was always there just waiting to smile. No one should have to wait that long to be themselves.

Outro

[00:29:41] Ashley: Thanks for listening. If you’re a paid Patreon member, stick around until the end of the credits for some bonus content. If you’re not, head to patreon.com/taboo science to join for as little as $5 a month.

[00:29:53] Ashley: Thank you so much to Aaron Devor, who spent extra time helping me understand this topic. If you wanna hear more from him, he has a great interview on Podcast for Inquiry. where he really explains the trans landscape. I’ll link it in the show notes.

[00:30:07] Ashley: Thank you also to Riley Black, Hibby Thach, and Charlie James.

[00:30:11] Ashley: Riley Black’s latest book is the Last Days of the Dinosaurs, and you can learn about her and her other books at RileyBlack.net

[00:30:18] Ashley: Hibby Thach’s website is HibbyThach.com. That’s H-I-B-B-Y-T-H-A-C H.com, where she shares her research about queer and trans people of colors’ online experiences with platforms and technologies, often within gaming related spaces like indie video game development and video game live streaming.

[00:30:39] Ashley: Charlie James is on TikTok at @MaleCowgirl, and he just came out with a book entitled, I’m Just A Little Guy, How To Escape The Horrors and Get Back to Dilly Dallying. You can learn more at CharlieJamesComedy.com.

[00:30:52] Ashley: You’ll hear more from all of them later in the season.

[00:30:55] Ashley: Taboo Science is written and produced by me, Ashley Hamer Pritchard. Our sensitivity reader is Newton Schottelkotte. The theme was by Danny Lopatka of DLC Music. Episode music is from Epidemic Sound.

[00:31:10] Ashley: The next episode is all about medical transition, hormones, surgeries, and everything that entails. You can catch that in two weeks. Hope you tune in. I won’t tell anyone.